A museum of captivity: what for?

A sensitive subject if ever there was one, on both the German and French sides, we decided to do this “freeze frame” to take a step back and answer the question that many people may be asking. Fabien Théofilakis, head of the scientific committee, summarizes three points of entry:

A museum first and foremost for history

With the first museum devoted entirely to the captivity of German soldiers, the aim is to raise awareness of a little-known history that lies at the heart of the world we live in:

- On the German side, the four camps evoke the fate of 11 million soldiers defeated in 1945 and, through them, that of the whole of post-defeat German society,

- On the French and Allied sides, considering the paradoxes of wartime captivity in peacetime, we emphasize the use of captive labor in the reconstruction effort. What happened in France, the UK and Poland, all the victors practiced in 1945: by having the ruins rebuilt by those who had destroyed them, they made the work of German prisoners a condition of Reconstruction.

But why is it important to tell this story? And why now?

A museum to help us understand how to emerge from war and build peace

Admittedly, the fate of German prisoners of war is just one of the many challenges of the post-World War II era, and certainly not one of the most painful. However, the oblivion in which this question remained for a long time, reinforced by the shame of defeat, obscured an issue specific to this necessarily dual history, that of the vanquished and the victor: German captives were above all perceived, at the Liberation, as Hitler’s soldiers. Their mass captivity therefore took on a fundamentally political dimension, which had an impact on the future of the Continent: how could we prevent the second post-war period from becoming, like the first after 1918, a new pre-war period? To succeed where Europe had failed 27 years earlier, millions of men had to be “reoriented”(reeducation / Umziehung), not only demobilized militarily, but also culturally, by abandoning Nazi ideology for democratic ideals.

A history museum in touch with current affairs: explaining the past through the present and vice versa

Captivity is thus seen as a crossroads in time and space. While the permanent exhibition focuses on the treatment of the vanquished of the Second World War – adopting a transnational perspective with four victorious powers – sections will be devoted to comparisons with earlier and later conflicts, while temporary exhibitions will explore very contemporary dimensions of captivity. As the tragedy of history reintroduces the figure of the captive to the European continent, the museum, in its own way, intends not only to explain the present through the past (where we come from), but also to show how the present shapes our understanding of the past and the questions we ask of it.

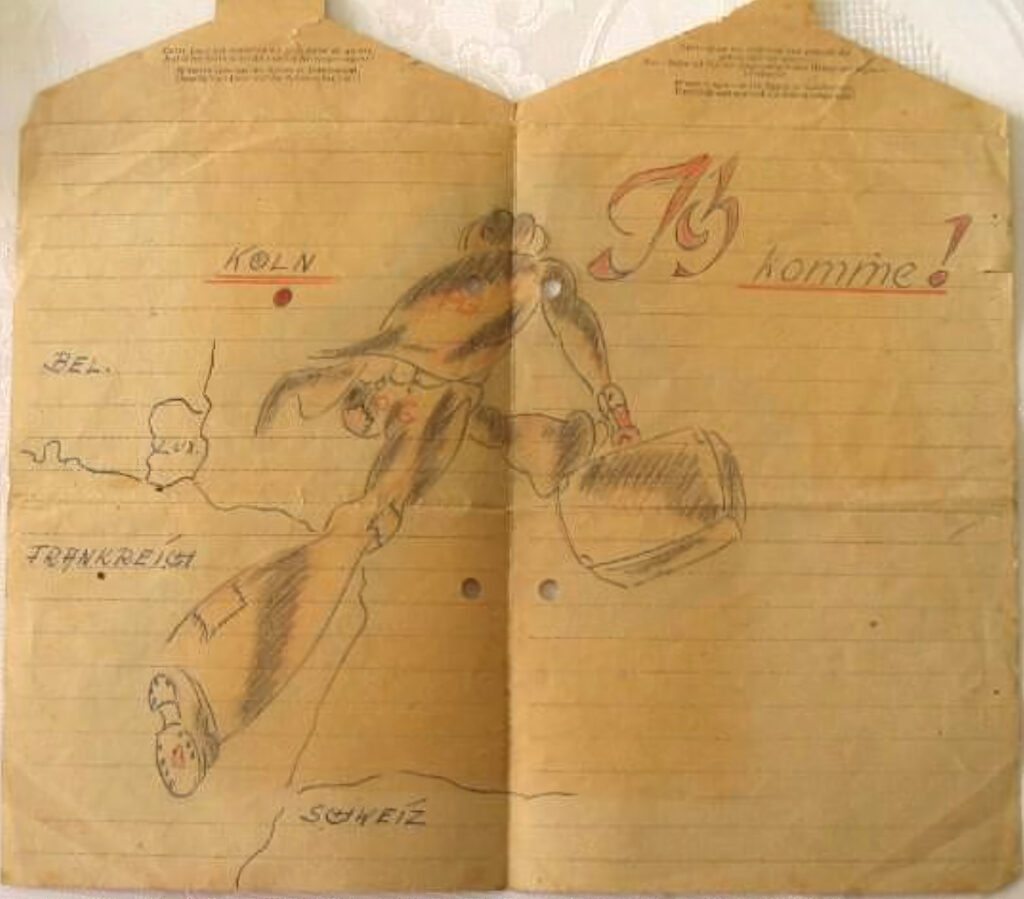

While we await the public’s response, the interest shown by the archive centers we’ve contacted in setting up partnerships for the loan of archives to illustrate the museum’s permanent tour, or to prepare future temporary exhibitions, leads us to believe that there are many fascinating archives slumbering in the shelves, just waiting to be brought to light by this open, comparative and transnational approach.

These prestigious archives include French institutions such as the Service Historique de la Défense (SHD), the Établissement de Communication et de Production Audiovisuelle de la Défense (ECPAD) and the Archives Départementales du Nord, as well as international ones such as the Bundesarchiv, the Deutches Tagebucharchiv (DTA) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).